Indigo Leaf

A Guide to Dried Indigo Leaf

Shepherd Textiles Indigo Leaf Natural Dye contains the raw dried leaves of the indigo plant, indigofera tinctoria. The leaves are very fresh—from either this year’s or last year’s harvest—and they have been only lightly crushed to the consistency of tea. As a result, they still contain the undamaged precursors of indigo blue, indican and beta-glucosidase. When the leaves are blended with ice water, the two precursors are combined and the chain reaction leading to indigo blue begins. Any protein fibers soaking in the cold water will be dyed beautiful shades of ice blue and turquoise as the reaction finishes. Please note that this method works on wool and silk, but not on cotton—use Indigo Extract instead. Our dried indigo leaf is grown in the USA and gives gorgeous ice blues on wool and silk at 100% weight-of-fabric.

1. Background on Indigo Leaf

Natural indigo is extracted from the leaves of indigofera tinctoria, a short shrub that is a member of the legume family. Indigo is now cultivated world-wide, but is probably native to South Asia (Glowacki et al. 2012:542). It has been the most important source of blue dye for much of recorded history, and there is archaeological evidence that indigo was being used to dye fabric up to 4,000 years ago in India. Natural indigo was a major global commodity in the 18th and 19th centuries, and industries sprang up all across the world. It was one of the major exports of the antebellum U.S. South, especially around low-country South Carolina and Georgia, which have subtropical climates ideal for growing indigo. However, a German chemist identified the chemical structure of indigotin and discovered how to synthesize it in 1883 (ibid:542). This lead to the collapse of the indigo-growing industry. Today indigo is still the most important blue dye for clothing and jeans, but almost all of it is synthetically produced indigo, not indigo extracted from a plant.

Indigo is unique among all natural dyes in how it attaches to fiber. Boiling it in hot water will have no effect, because the blue coloring compound indigotin is insoluble in normal water. The traditional method of applying it involves fermenting the leaves, extracting the dyestuff, dissolving it in a reduction vat, and then dipping fabric in the vat. When fabric is removed from the vat, the dissolved indigotin oxidizes and comes back out of solution, bonding immediately to the fiber. However, it is possible to short-circuit this laborious process by taking advantage of the chemistry of indigo leaves.

Indigo does not exist in the plant in the form of blue indigotin—otherwise the plant itself would be blue. Instead, it exists in the form of two precursors, beta-glucosidase and indican. If the leaf is damaged by grazing herbivores or gnawed by insects, the precursors are mixed together and blue indigotin forms. This may have evolved as a defense mechanism against predation, although the evidence is unclear (Daykin 2011:5). If high-quality indigo leaves are harvested very carefully, the two precursors are preserved even after the leaves are dried. They can later be blended with ice water to mix the precursor compounds and begin the chemical reaction leading to blue indigotin. As the cold water warms up, the beta-glucosidase cleaves the indican into a molecule of indoxyl, and the indoxyl reacts with oxygen dissolved in the water to form blue indigotin. Any wool or silk soaking in the water while this reaction occurs will be dyed blue, too. Using fresh indigo leaves it is possible to achieve beautiful shades of turquoise and ice blue, without needing to build a reduction vat.

Nature’s Strongest Blue

2. Safety Precautions

DO NOT INGEST. This product is intended for textile dyeing, not as an herbal supplement.

Avoid eye contact. If eye contact occurs, rinse with cool water.

Not for use as a cosmetic additive; do not apply directly to skin or hair.

If a spill occurs, quickly wipe up with a paper towel or disposable rag.

Use only dye pots and utensils dedicated to dyeing. Do not use any pots, containers, spoons, tongs, thermometers, or other utensils that will be used for food preparation.

Dried indigo leaf, and all dye baths and mordant liquors made while dyeing, should be kept out of reach of children and pets. Use only with adult supervision.

Shepherd Textiles, LLC is not liable for any misuse of this product or any unintended staining of your clothing, workspace, or other property. Use only as directed.

3. Recommended Supplies

Dye pot. Use a dye pot large enough to hold all your fibers, with plenty of room for them to move around and for the liquid to circulate freely.

Metal tongs. A pair of tongs is useful for stirring and taking fabric out. Use tongs dedicated to dyeing, and not for food preparation.

Rubber gloves. Wear rubber gloves while removing fibers from the indigo solution—when it is nearing completion, it can stain your hands blue.

Scale. Use a scale to weigh out fiber and dyestuff.

Blender. The indigo leaves will have to be blended with water; if possible, we recommend using a blender that is reserved for dyeing and not for food preparation.

Strainer. The ground indigo leaves will need to be strained out of the dyeing solution. We strain once through a metal strainer, then again through a coffee filter; cheesecloth would also probably work.

4. Preparation: Scour (Clean) the Fiber

Indigo bonds to fiber at the molecular level and does not require any mordanting. However, this is one dye where you want to be absolutely certain your fibers are scoured clean before you begin. With hot-dyeing, sometimes you can get away with not scouring your fibers completely because the heat of the dyebath will disperse minor bits of grime. Since this is a cold-dyeing method, however, any dirt on the fiber—including oily fingerprints, sweat stains, and lanolin—will become hugely obvious on the finished product.

For protein fibers (wool, silk, alpaca, etc.): Scour with a PH-neutral detergent or a wool scour.

Fill a dye pot 3/4 full with warm water. Add a teaspoon of PH-neutral detergent like Synthrapol. Alternately, use a product sold specifically as a wool scour or silk degummer. Mix well until fully dissolved.

Add the fibers to be scoured.

Raise the heat to 160F (for silk) or 180F (for wool or alpaca). Hold for 30 minutes, stirring regularly but gently (you do not want to felt your wool).

After half an hour, lift the fiber out with tongs and rinse in hot water that is the same temperature as the scour bath. This will prevent thermal shocks that damage the fiber. We usually have a second dye pot full of hot water, heated to the same temperature as the scour bath, to plunge the fibers into.

Let the fibers cool to room temperature, then squeeze out excess water while wearing rubber gloves (you do not want to the oil in your fingerprints to attach to the newly cleaned fiber).

Proceed with dyeing.

The Recipe

5. Recipe: Ice Blue

The basic recipe for Indigo Leaf is to blend 100% weight-of-fabric of the crushed leaves with ice water to create a dark green dye bath. As the cold bath slowly heats up, the chemical reaction leading to indigo blue will begin. Protein fibers soaking in this liquid will slowly turn blue as well. For the darkest blues, leave the fibers in until the reaction is complete and the dyebath water has turned a dark midnight blue. For lighter shades, remove the fibers as soon as the desired color is achieved, although note that the fibers will look a few shades lighter when dried than they did when wet.

Weigh out 100% weight-of-fabric (WOF) of dried indigo leaf.

Fill a blender half full with cold water—you can use cold water from the tap or, if you have it, cold water from the refrigerator.

Add a small handful of ice cubes and blend for 30 seconds. The colder the water is, the more time you will have to finish straining and building the dye bath before the reaction starts.

Add the dried indigo leaf and blend for 1 minute. The water in the blender should be dark green, with some white froth on top.

Strain the green liquid into the dye bath, using a fine mesh strainer or cheesecloth.

Return any strained indigo leaf to the blender. Fill it again half-way full with cold water and a few ice cubes. Blend for another minute, and once again strain the green liquid into the dye bath.

Repeat the extraction one or two more times to get as much indican as possible out of the leaves.

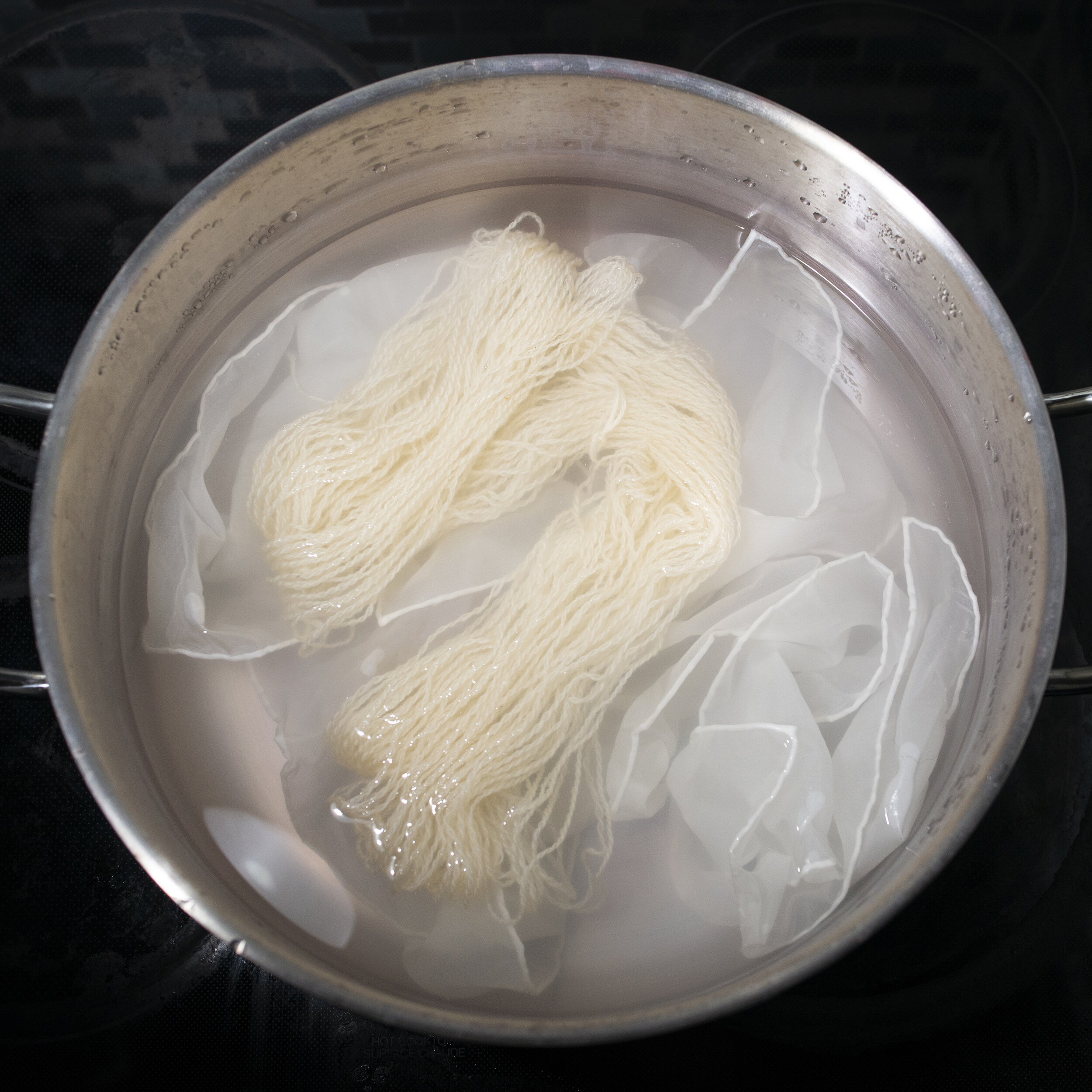

Add your well-scoured, pre-soaked fibers to the green dye bath.

Wait. As the dyebath warms toward room temperature, the beta-glucosidase will begin to cleave the the indican into indoxyl, which will quickly react with the oxygen dissolved in the water to form blue indigo. When the fibers begin to take on a tiny hint of turquoise color, the reaction is beginning.

Every half our or so, stir the fibers so they dye evenly. You may wish to lift them out of the dye bath for a minute or so, so that oxygen in the air can accelerate the bonding of the indigo to the fiber. Expect it to take at least 3 or 4 hours for the reaction to complete.

When the fibers have achieved a desired depth of shade, remove and rinse lightly in lukewarm water, then hang up to dry to help set the color.

When the dyebath turns a dark midnight blue, that means all the indican has converted to indigotin and there is none left to apply to the fibers. At this point, all the fibers should be removed and rinsed.

For the final rinsing, we recommend using a PH-neutral detergent like Synthrapol, which is designed to wash out loose dye. Follow the manufacturer’s directions for best results. CAUTION: Indigo will bleed if not thoroughly rinsed out after dyeing.

Hang up to dry out of direct sunlight.

Step 4. Blending the dried leaves with cold water and a few ice cubes will create a frothy, dark green liquid. Strain off and repeat two times.

Step 8. When the fibers go in the bath, it should be a dark olive green; this means the reaction leading to indigotin has not started yet.

Step 10. As the water warms up to room temperature and indigotin forms, the bath will slowly turn blue—and so will the fibers soaking in it.

All images and text are copyright of Shepherd Textiles, LLC. Do not reproduce without written permission and attribution.